THE JOURNAL

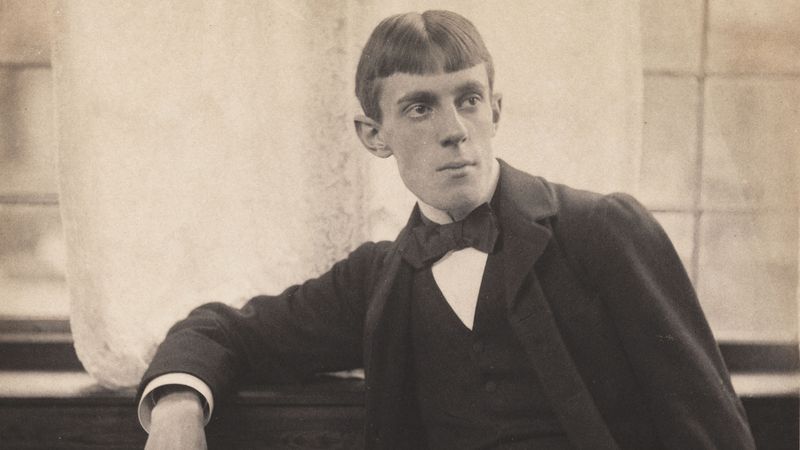

Mr Aubrey Beardsley photographed in a London studio, c 1895. Photograph by Mr Frederick Hollyer/The Royal Photographic Society/Getty Images

Mr Aubrey Beardsley liked to make a splash. The great Art Nouveau illustrator and art editor of The Yellow Book, the periodical of the Decadent (a rather self-explanatory creative movement in the late 1900s), spent his whole life flouting convention. And he did this, perhaps, because what did he have to lose? He was, after all, in a race with death. Born in Brighton in August 1872, by the age of seven he had been diagnosed with tuberculosis, the disease that killed his father and grandfather. He would be dead, in appalling pain, at 25.

“I am now 18 years old,” he wrote to his former housemaster in 1890, “with a vile constitution, a sallow face and sunken eyes, long red hair, a shuffling gait and a stoop.” At the age of majority, he knew he wasn’t long for the world, and so, naturally, he set about courting attention and outraging Victorian society.

“Mr Beardsley, above all others, understood the power of image, the strength of the brand”

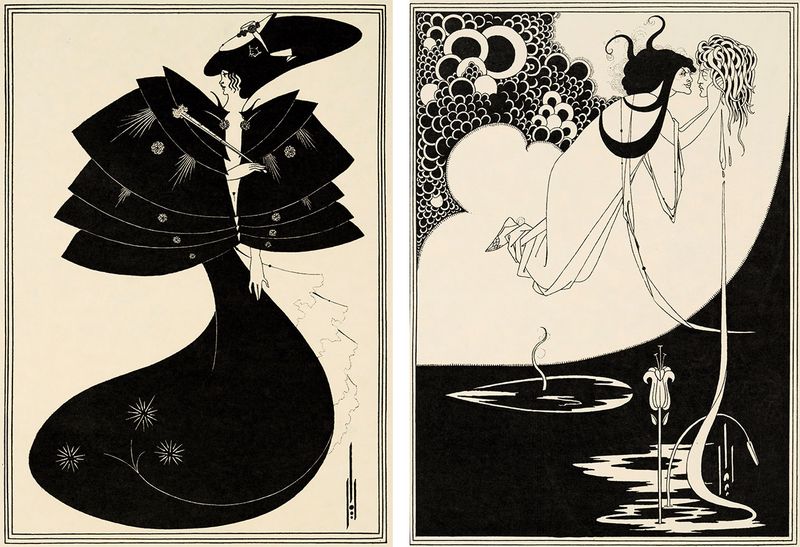

Buttocks, beheadings, breasts and erections – Mr Beardsley rendered them all in his sinuous Japanese-influenced style. They can still alarm today. Tate Britain will bring together hundreds of his drawings and woodcuts, in a retrospective of his work next month. They are beautiful and witty and wholly filthy. His work, while aesthetically beautiful and stylistically unique, mocked ideas of propriety and questioned every norm of sexuality and gender. His famous “Toilet of Lampito”, for example, features a woman in stockings bending over as a priapic Eros powders her bare bottom. Victorian ladies may have reached for the smelling salts, but artists such as Messrs Edvard Munch and Pablo Picasso were inspired.

Mr Beardsley learnt the value of provocation from his mentor Mr Oscar Wilde and to épater the bourgeoisie became Mr Beardsley’s métier. Sadly, Mr Wilde épatered a touch too much and ended up carted off to Reading jail. Nevertheless, Mr Beardsley had learnt what he needed from Mr Wilde.

From left: “The Black Cape”, illustration for Mr Oscar Wilde’s Salome, by Mr Aubrey Beardsley, 1893. Photograph courtesy of Tate Britain. “The Climax”, illustration for Mr Oscar Wilde’s Salome, by Mr Aubrey Beardsley, 1893. Photograph courtesy of Tate Britain

He had also, apparently, stolen his hairdresser. If you examine the follicles of Mr Beardsley and Mr Wilde, you might see some similarities. They were both fond of a central parting; they both looked quite severe. Their dress sense was similar, too; for they both favoured the tailor Doré, though Mr Beardsley’s dandyism was more modern. He made his sartorial splash more subtly than Mr Wilde, favouring cinched waists and oversized bow ties, rather than furs and affected canes.

Shorn of his Victorian morning suit, Mr Beardsley would look strangely contemporary. His nonchalant gaze away from the camera, the long fingers lolling down as he leans back on the photographer’s bench, and his precise, symmetrical haircut – it might easily be a Vetements campaign. Mr Beardsley, above all others, understood the power of image, the strength of the brand. And in that way, he was a man before his time, a curiously modern Victorian.

The last word on him deserves to be his sister Ms Mabel Beardsley’s pinpoint rendering of him. As she lay dying, she turned to her great friend Mr WB Yeats, and said, “I wonder who will introduce me in heaven. It should be my brother, but then they might not appreciate the introduction. They might not have good taste.”