THE JOURNAL

Rolex is one of the best-known brands in the world. For good reason – despite making more than 2,000 products per day, all retailing well into the thousands, pound-for-pound they’re among the most reliable and best-built Swiss watch brands on the market.

But when it comes to the “finest”? That’s another matter entirely. We’re talking the exclusive production of first-class, hand-finished mechanical timepieces, crafted in that romantic way we imagine all Swiss watchmaking to be completed: hunched artisan, magnifying glass glued to his eye, tweezers in hand, cowbells clanking through his atelier window.

Tiny components may be “roughed out” by computer-controlled machines these days, but the polishing, assembly and fine adjustment is still painstakingly practised in handmade fashion, and there are only five maisons who can do it all under their own roofs. These so-called “manufactures” are Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Jaeger-LeCoultre, Audemars Piguet and Girard-Perregaux, and for well over a century – non-stop – every watch that’s left their workshops has been nothing less than pure luxury.

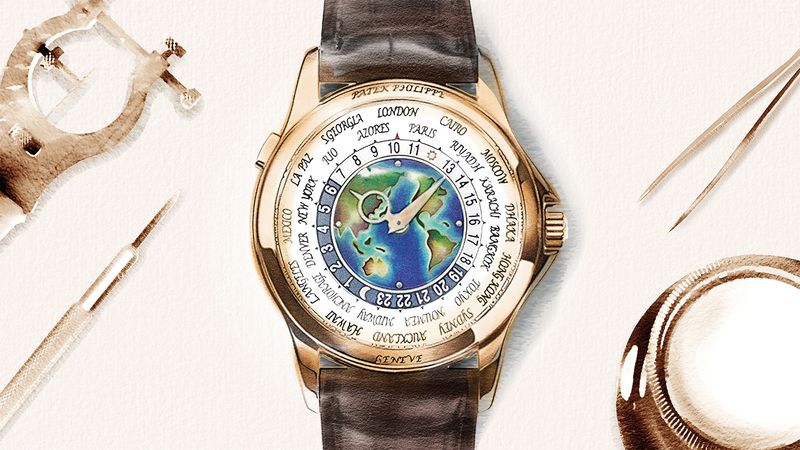

Patek Philippe

If Rolex is the brand every beginner wants, Patek Philippe is the brand most aspire to. In 175 years, Patek has soared through world wars, recessions and near collapse during the Great Depression (when current owners and former dial-makers, the Stern family, bought the business) to qualify as Switzerland’s grande dame. It is the most investment-friendly, if auction-house records are anything to go by (seven of the top 10 watches sold at auction are by Patek), underpinning its legendary slogan, “You never actually own a Patek Philippe. You merely look after it for the next generation”.

Set up by Polish immigrant Mr Antoni Patek and Mr Jean Adrien Philippe in 1851, the Dior of watchmaking has always adhered to one simple business plan: to make the most beautiful and valuable watches in the world. In the process, it has pioneered the winding crown, made the first Swiss wristwatch (for a countess), and mastered every one of horology’s finicky “complications” – often in combination with each other, as 1989’s 150th-anniversary Calibre 89 pocket watch proved. Its 33-count of complications smashed records, thanks to Patek’s forward-thinking investment in computer-aided design (back then, anathema to dyed-in-the-wool watchmakers), but its headline-grabbing $3.17m sale also heralded the return of our fascination with traditional watchmaking, after two devastating decades of newfangled quartz technology. More recently, Patek Philippe has also emerged as one of the leading exponents of silicon technology, replacing the vulnerable metal components of the tick-tick-ticking “balance assembly” with the anti-magnetic, self-lubricating material. Progressive, as always, but with Patek’s commitment to classicism.

Vacheron Constantin

Nothing – not the French Revolution, nor the Battle of Waterloo, nor two world wars – has stopped Vacheron Constantin from producing watches every year since 1755. The only rival to Patek Philippe’s status as “Geneva’s favourite son” makes classic dress styles, jewellery pieces and even surprisingly sporty designs, but ultimately Vacheron’s reputation is built on a history of exceptionally complicated watches. It currently holds the record for most complicated watch ever made – 2015’s Ref 57260, which houses 57 complications. (Needless to say its 98mm diameter is ill-suited to wrists, and most pockets if we’re honest.) Like Patek, Vacheron’s watches bear a purism that feels more Latin, more cosmopolitan than its contemporaries – in most part down to the brand’s continued foothold in the heart of Geneva itself, rather than the outlying Jura mountains. It was there, on an island in the Rhône river, that Mr Jean-Marc Vacheron opened his atelier in 1755. Remaining as the brand’s spiritual home, manufacturing and HQ has meanwhile relocated somewhere completely different: a hyper-architectural “folded” building designed by Mr Bernard Tschumi in 2004, in Geneva’s industrial suburbs – next-door to Patek, funnily enough. Wholly owned by the Richemont Group, Vacheron Constantin is a grande maison in the truest sense – a master of every high-horological complication as well as a virtuoso in the decorative crafts.

Jaeger-LeCoultre

Perched on the shores of Lac de Joux, the view from Jaeger-LeCoultre’s ateliers has barely changed since Mr Antoine LeCoultre settled on this exact same spot 180 years ago. The go-to manufacturer of precision movements for many of Switzerland’s best brands, it fell to Mr LeCoultre’s third generation to team up with French marine-clock maestro, Mr Edmond Jaeger, in the early 20th century, creating the brand we know now: Swiss technical expertise endowed with a Parisian aesthetic. The fact that Jaeger-LeCoultre started out not making its own watches but rather the inner mechanics for other brands means it’s often excluded from lists like this. These “movements” are among the best, however. They and their surrounding dials and cases are all created beneath one roof, from the raw metal, demanding a mastery of 180 individual skills. They have earned the company its anecdotal status as the “watchmaker’s watchmaker” and “Switzerland’s Grande Maison”. Entry to the Big Five came thanks to its ever-diversifying portfolio of classics: the Art Deco-era Reverso (flippable to survive polo matches on the fields of the British Raj), the tiny Caliber 101 (worn by the Queen at her coronation in 1953) and the development of the balletic Gyrotourbillon, one of which uses four sets of gongs and hammers to recreate the chimes of Big Ben – we kid you not.

Audemars Piguet

It was a classic case of having too much work and not enough time. To cope with demand for his ingenious mechanics from Geneva’s highfalutin watchmakers, Mr Jules-Louis Audemars recruited talented young buck Mr Edward Piguet. By 1875, they’d shunned their clients and turned a white-label enterprise into a brand in its own right, albeit in a sleepy Joux Valley village, where Audemars Piguet remains today – still proudly independent at the hands of the Audemars family.

Far-out complicated watches are still a speciality, thanks in part to owning maverick micro-mechanical wizards Renaud & Papi over the hills in Le Locle. But the modern brand is best known for inventing the luxury steel sports watch as we know it, back in 1972: the still-iconic, octagonal Royal Oak. It was more expensive than its gold equivalent on launch, owing to the tricksy machining required for all its curves, edges and integrated bracelet, but defied all odds to become a best-selling classic. The watch is famously accredited to designer Mr Gérald Genta. But just look at how AP has taken the mighty Oak and run with it, often in concert with stopwatch, calendar, chiming or tourbillon features, and occasionally with all four. With 1994’s pumped-up, cuff-busting Offshore version, the Royal Oak also managed to invent the “outsize’” trend that persists to this day, from the decks of Monaco yachts to every hip-hop video going.

Girard-Perregaux

Here’s your curveball – the entry most likely to furrow brows. Whether you consider Girard-Perregaux too “boutique” to be keeping company with the above grandmasters, one thing is irrefutable: the brand has serious, unbroken heritage dating back to 1791, it is a true manufacture that hand-finishes its movements to first-class standards, and it has mastered every major complication while pioneering a few of its own. It had its own Nautilus/Royal Oak moment in the 1970s, bursting onto the new luxury steel sports watch scene with its own octagonal Laureato.

It was something of a two-pronged irony, therefore, that the company was not only the first to mass-produce quartz timepieces in Switzerland, establishing quartz’s now-standard oscillating frequency of 32,768Hz, but also one of the first to abruptly cease all R&D in that area and return to mechanical craftsmanship – in 1981, when the Swiss craft was at its lowest ebb, cheaper quartz having decimated its collective workforce by a third.

To set out their stall? A reissue of their iconic 19th-century pocket watch, the Tourbillon with Three Gold Bridges: winding barrel, gear train and tourbillon carriage each suspended from an intricately sculpted golden bridge. Gleaming horological theatrics, ushering in the brand’s new age of haute horlogerie, the Three Gold Bridges is now an icon in its own right, presiding over a distinguished portfolio of slender cocktail numbers, diving watches and another modern classic, its WW.TC model.

Illustrations by Mr Jaume Vilardell