THE JOURNAL

Whether you’re dining upmarket or are happy to stay at street level, it doesn’t take long to realise that the term “Japanese cuisine” covers a huge spectrum of dishes and numerous styles of cooking; that most restaurants tend to specialise in one particular genre, or even a single main ingredient; and that, by and large, whatever food is being prepared, the attention to detail and quality is remarkable.

Here are seven dishes to look out for — and that deserve a special trip across town next time you find yourself in Tokyo. A few are traditional, some are a lot more contemporary. Others mark the changing seasons. Most are year-round classics that celebrate the remarkable diversity of Japanese food.

01.

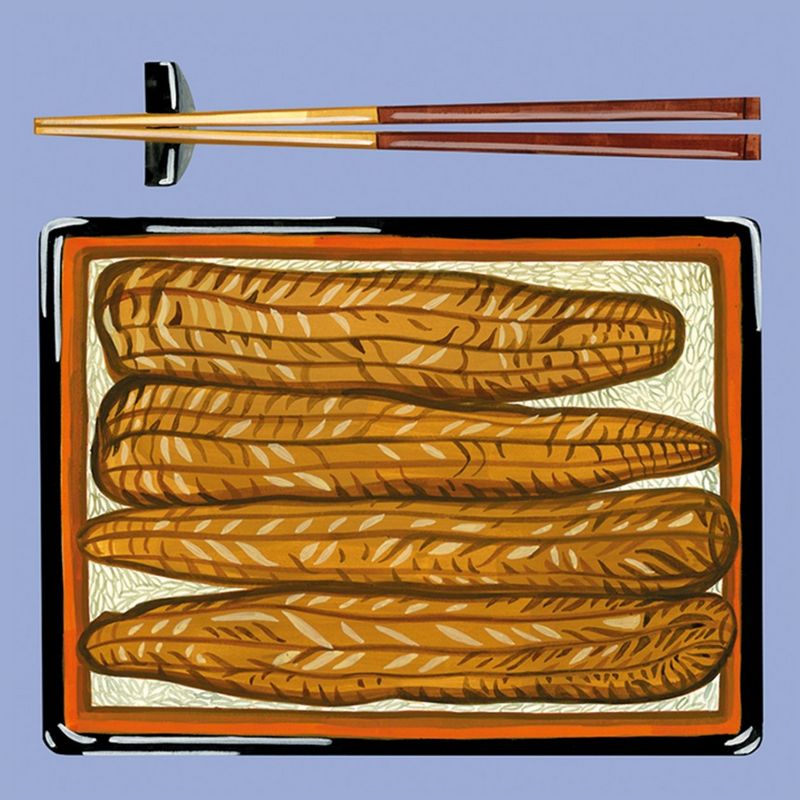

Unagi kabayaki

Eel is often seen as an unrefined fish. It is fatty and earthy, with a bony structure that can be challenging to cook with and eat. But in the hands of inventive Japanese chefs, it is a star ingredient.

This classic recipe, known as unagi (eel) kabayaki, is underappreciated outside of Japan. The eels are deftly filleted and spitchcocked on bamboo skewers, then lightly grilled, steamed, and finally broiled again with occasional dips in a soy-based basting sauce, until each piece is tender and a rich golden brown.

Usually the fillets are served on hot rice inside a rectangular lacquer box with a lid to keep it piping hot. On the side you will find cruets of powdered sansho, a seed with a numbing spiciness akin to Sichuan pepper, and clear soup containing a whole eel liver, which is reputed to do wonders for your eyesight.

In Tokyo, there is no better or more traditional place to eat unagi than at Obana. But be prepared: no reservations are taken and the lines are long, especially in midsummer.

Obana

5 Chome-33-1 Minamisenju, Arakawa City, Tokyo 116-0003, Japan

02.

Gunkan maki

For connoisseurs in Japan, it’s one of the highlights of any sushi dinner: a small patty of rice, enclosed inside a crisp band of nori seaweed, topped with creamy tongues of orange uni (sea urchin) or glistening orbs of red ikura (salmon roe) – or perhaps even both together in the same decadent mouthful.

Known as gunkan maki (literally “battleship roll”), it feels more special than the regular one-bite, fish-on-rice nigiri sushi. Especially if the fish is as fresh as possible. Subpar urchin is enough to put you off sushi for life. But the good stuff, lifted just hours earlier from the ocean off Hokkaido, is incredible.

It’s not hard to find quality gunkan maki in Tokyo, especially at Kyubey, in Ginza. After all, it was invented there, back in 1941. It remains the signature bite and the perfect reason for a visit. Kyubey is a good place to start plumbing the depths of Japan’s sushi culture.

Kyubey

8 Chome-7-6 Ginza, Chuo City, Tokyo 104-0061

03.

Matsutake dobin mushi

Autumn in Japan brings dramatic fall foliage. But more than anything, it is mushroom season, when foragers head into the woods in search of wild fungi. If they’re lucky, they will chance upon matsutake, large pine mushrooms famed for their meaty caps and musky aroma.

The finest specimens are prohibitively expensive, often more than £100 apiece. But they rarely appear in shops. Instead, the foragers ship them directly to top traditional kaiseki restaurants, such as Nihonryori Ryugin in Tokyo, or Kyoto’s superb Kitcho.

As with truffles, the allure is in the smell, and Japanese cuisine has developed many techniques to maximize the mushrooms’ aroma. Matsutake are wonderful when grilled over charcoal. But during this season, the recipe of choice is usually dobin mushi.

Pottery vessels resembling small teapots are filled with fragrant dashi broth, along with morsels of chicken, shrimp or perhaps turtle, with fresh-season ginkgo nuts and matsutake taking pride of place. A dash of green sudachi citron, a leaf or two of mitsuba (trefoil)… let the steam waft up: that is the smell of autumn in Japan.

Nihonryori Ryugin

7F Tokyo Midtown Hibiya, 1-1-2 Yurakucho, Chiyoda-Ku, Tokyo 100-0006

04.

Creamed crab croquette burger

Picture this: a deep-fried croquette of generous dimensions, crispy and golden, filled with creamy, soft crabmeat. Now envisage it positioned between two lightly toasted burger buns with fixings of tomato, coleslaw and honey-mustard sauce. It stands as tall as your hand’s span.

It gets better yet. For a small supplement, you can order a special version of this premium burger that comes with kani miso, the dark, rich, savory tomalley from the crab shell. It’s a masterstroke that elevates the dish from great to superb, and makes it the standout item at Deli Fu Cious in Higashiyama.

Deli Fu Cious

1 Chome-9-13 Higashiyama, Meguro City

05.

Sansai tempura

In the spring, at just about any Japanese restaurant, your meal is likely to feature sansai, the edible wild plants that emerge in the woods and uplands as the snow retreats.

Foraging is not a recent gastronomic fad in Japan. For centuries, rural communities have survived on plants such as fukinoto, the flower buds of the butterbur plant; garlicky gyoja ninniku, a wild allium related to ramps; taranome, the first tender young leaves of the angelica shrub; and kogomi, the tightly furled fronds of the oyster fern.

To temper the intensity of their flavours, often sharply bitter or floral, the classic way of cooking these plants is to deep-fry them in a light tempura batter. Pair this with a simple serving of soba (buckwheat noodles), preferably hand-chopped by a master of the art, such as Mr Tadashi Hosokawa.

There are always lines outside his humble restaurant, Edo Soba Hosokawa, in eastern Tokyo. But they are longer than ever during the short window that sansai are in season.

Edo Soba Hosokawa

1 Chome-6-5 Kamezawa, Sumida City, Tokyo 130-0014

06.

Fugu karaage

There is a powerful, mystique surrounding fugu, the legendary puffer fish. And rightly so, given that its internal organs are laced with tetrodotoxin, a poison lethal in even small amounts unless removed with care by trained and certified chefs.

And yet, the thing about fugu that’s too often overlooked is that its flesh is essentially tasteless. The only way to make fugu really pleasurable is by cooking it karaage style, dusted in flour and then deep-fried until the coating is crisp and golden brown and the white meat of the fillets is beautifully soft and fluffy.

This exact same recipe is used at Den – currently Tokyo’s hottest restaurant – for cooking its famed chicken wings. Which is why, when pescatarians go to eat there, they are given fugu instead. Just call it Dentucky Fried Chicken of the Sea…

Den

150-0001 Tokyo, Shibuya City, Jingumae, 2 Chome−3−18

07.

Maboroshi gyutan

Mr Kentaro Nakahara is a master of the art of grilling beef. Not any old meat, mind you: he specialises in premium wagyu, the richly marbled, buttery-mild meat of Japan’s famously pampered black-coated cattle. That’s what distinguishes his restaurant, Sumibiyakiniku Nakahara, from yakiniku (“grilled meat”) joints across Japan.

He offers a remarkable variety of cuts. In fact his omakase tasting menu is an expert’s tour of the finest parts, some better known, others rarely seen, all identified by their Japanese names: zabuton, misuji, uchimono, kata sankaku and more.

His most remarkable offering is his maboroshi gyutan (“legendary beef tongue”). It’s a flight of three cuts taken from the tip, the underside and the base of the tongue. Grilled in front of you over a charcoal burner in the table, each part is subtly different in texture and flavour. You will find nothing like it anywhere else.

Sumibiyakiniku Nakahara

102-0085 Tokyo, Chiyoda City, Rokubancho, 4-3 GEMS

Illustrations by Ms Fanny Gentle