THE JOURNAL

Metropolis, 2001. Photograph by Toho/Tezuka/REX Shutterstock

From Akira to Wolf Children – the manga to watch instead of (or alongside) Ghost And The Shell.

Japan has more than 400 production companies dedicated to anime. While this represents a relatively small part of Japan’s film production as a whole – roughly 10 per cent – anime is nonetheless one of its greatest cultural exports. And in 2017, it’s only getting more mainstream.

This month marks the release of Ghost In The Shell, a Ms Scarlett Johansson-led, live-action Hollywood remake of the classic 1995 anime directed by Mr Mamoru Oshii, itself based on a Manga comic book. The Hollywood version has been in production for more than 10 years, with the British director Mr Rupert Sanders, best known for Snow White And The Huntsman, drafted in as director. It seems the production company, Paramount, is hoping it will be The Matrix of the millennial generation.

The casting of Ms Johansson in the lead role has created controversy, amid accusations of whitewashing and allegations that CGI was used to make her look more ethnically Asian during the film’s production. Some 103,000 people signed a petition calling for the role to be re-cast with a Japanese actress.

Writing for Asia Times, critic Mr Pavan Shamdasani said of the film: “The original is about as Asian as things get: Japanese cult manga, ground-breaking anime, Hong Kong-inspired locations, Eastern philosophy-based story. Most of that’s been downright ignored with its big-screen adaptation, and Scarlett Johansson’s casting as the dark-haired, obviously originally Asian lead sent netizens into a rage.”

All of which is a long-winded way of saying that if you’re curious about the huge and rather bounteous world of anime, then perhaps this latest blockbuster is not the best place to start (although, let’s face it, we’re probably all going to go and see it). As Tinseltown pays its homage to a remarkable sub-genre, here’s MR PORTER’s guide to the five anime films you should really (or also) be watching this week.

Perfect Blue (1997)

Perfect Blue, 1997. Photograph by REX Shutterstock

If you thought anime was all cute animals and blaring mecha-suits, Perfect Blue is a fine demonstration that it runs the gamut of every genre, and can even do nail-biting horror. Based on the novel Perfect Blue: Complete Metamorphosis by Mr Yoshikazu Takeuchi, the film follows Mima Kirigoe, a 21-year-old pop idol turned actress, who discovers she is being stalked. The stress of the experience triggers a deep immersion into her first fictional role. As the role and her real life start to blend and fuse, we’re given a disquieting look into the darker recesses of Japanese culture, where so many TV-ready children are made to look like fantasy dolls.

Akira (1988)

Akira, 1988. Photograph by Akira Committee/Pioneer Ent./REX Shutterstock

Akira is the grandaddy of Japanese anime. It’s considered to be a landmark in Japanese animation, and said by critics and cult fans to be one of the greatest science-fiction movies of all time. Directed and written by Mr Katsuhiro Otomo, and based on his manga of the same name, this bold, often bizarre film is set in the almost present future, and depicts a dystopian, cyberpunk Tokyo in 2019.

Our hero is teenage biker Tetsuo Shima and his gang leader, Shotaro Kaneda, both of whom fall foul of a shady government agency when Tetsuo discovers he has some disturbing telekinetic powers. Without giving anything away, let’s just say it snowballs from there, unfolding in an eye-popping continuum of fast bikes, white-hot explosions and collapsing buildings, all rendered with such incredible frenetic detail that it’s actually a little exhausting to watch. It’s a landmark film in Japanese anime, as interested in style as it is in substance, and fully capable of using animation to create stunning set pieces that would never be possible in any other medium.

Ponyo (2008)

Ponyo, 2008. Photograph by Collection Christophel/ArenaPAL

Originally entitled Gake No Ue Ponyo (“Ponyo On The Cliff”), this is the eighth film legendary animator Mr Hayao Miyazaki directed for Studio Ghibli, the studio behind crossover hit Spirited Away and children’s classic My Neighbor Totoro. Ponyo may not be Mr Miyazaki’s most celebrated film, but you’d be hard-pressed to find a Ghibli film that’s more charming, gentle and artful.

Ponyo is a goldfish who wants to become a human girl, and who is saved on the beach by a five-year-old boy, Sōsuke, who lives by the sea with his hard-pressed mother and his father, a sailor who is often away. But Ponyo has powers capable of creating a tsunami-like shift in the world’s elements, and soon Sōsuke finds himself on an adventure through the depths of the sea.

If you’ve never sat down and spent time in the imagined worlds of Mr Miyazaki, this is where to start. Grab yourself the nearest smiling child, settle down with the DVD, and strap in.

Wolf Children (2012)

Wolf Children, 2012. Photograph by Photo 12/Alamy

Hana, a young mother, is left to raise her two children, Ame and Yuki, after their father dies. One thing to note – their dad was a werewolf. So, while she raises children capable of becoming wolves, she also must keep the wolf from the door – literally.

The children’s hybridity between human and beast is played upon frequently, but this film is, at heart, a portrait of a woman’s determination to love, nurture and prepare her kids for the wider world, whatever their appearance and whatever their shortcomings. It’s a powerful expression of humanity, caught in a magical realist fantasy.

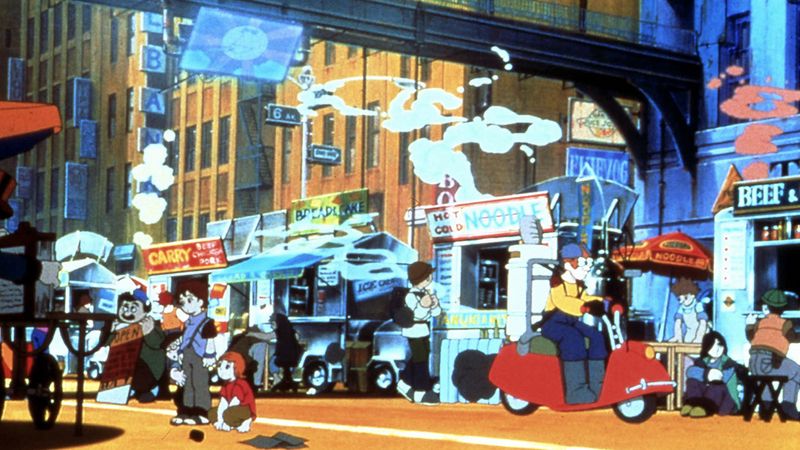

Metropolis (2001)

Metropolis, 2001. Photograph by Collection Christophel/ArenaPAL

Metropolis is loosely based on the 1949 Metropolis manga created by Mr Osamu Tezuka, itself inspired by the 1927 expressionist German silent film of the same name, directed by Mr Fritz Lang. It’s written by Akira’s Mr Otomo and directed by Rintaro.

For all its madness, Metropolis remains a relevant, even prescient film, that depicts a futuristic mega city in which elitist politicians (who live on the surface), vie for control of the dispossessed robot masses, who are confined to underground zones. The city itself is stunning – a psychedelic retro-future in which high-tech meets art deco – and Rintaro’s infusion of noirish tropes into the sci-fi setting recalls films such as Sir Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner or even Mr Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville. Newcomers to anime might find it all a bit much – especially the grandiose, kaleidoscopic plotting, which develops over multiple narrative threads – but for if you’re looking for a cheap legal high, there are few better examples of the genre at its most joyously unencumbered.