THE JOURNAL

Anyone who grew up during a very specific moment – a time of MySpace and those belts, you know those belts, with the indeterminate length of woven canvas that hung down – will have a particular affinity for Vans, the sneaker and skating giant founded in 1966 by brothers Messrs Paul and Jim Van Doren. The shoes’ revival in the 2000s was a saving grace for a company that had already suffered through bankruptcy and was struggling to compete in the shadow of sportswear superbrands. So, how did the business turn the tide? It did what many other flailing labels were doing at the time: it went back to its roots.

Revisiting iconic styles from its archive – the Era, checkerboard slip-on and, our subject for today, the #44, now known as the Authentic – would prove successful with a generation that had taken to referring to thrift stores as vintage shops and had clandestinely pinched their dad’s Wayfarers. Retro was back. And it hasn’t budged since. The question remains, though, how did Vans manage it, when the proliferation of other purveyors of canvas and rubber sneakers couldn’t?

For starters, the Van Doren clan knew its sneakers. “It was a business that my grandmother worked,” says Mr Steve Van Doren, son of the brand’s co-founder Mr Paul Van Doren and the company’s current vice president of events and promotions. “She was a sewer at a factory that was close to where they lived south of Boston. My grandmother got my dad a job there sweeping the floors when he dropped out of school at 16 years old.” Two decades later, Mr Paul Van Doren was the label’s senior vice president.

It was during his time at the factory that Mr Paul Van Doren noticed a problem with the sneaker business model. As it stood, the industry was based on a supplier-to-store template, a scheme that divided profits between the makers and the sellers. But he had a plan that would break the mould: Mr Van Doren and his brother, Jim, would sell the sneakers they made from their factory direct to the customer, cutting out shipping overheads and store-running costs.

With Messrs George Lee and Serge D’Elia on board as investors, the Van Doren Rubber Company, as it was then known, next faced the tall task of finding the right location – a place with enough foot traffic to draw in window-shoppers, but also ample space to accommodate heavy machinery. In Anaheim, a mile down the road from Disneyland, they found the perfect spot. That they settled on Southern California, home to a burgeoning surfing and skateboarding community, would prove to be an incredible stroke of good luck.

Exterior of Anaheim Shop Front and Factory, California, 1966. Photograph courtesy of Vans

“With an impressively sturdy shoe in its arsenal, it wasn’t long before the skateboarders came knocking”

Mr Steve Van Doren was just 11 years old on 16 March 1966 when the flagship store on 704 E Broadway first opened its doors, but his memories of the early days are vivid. You’d think being the boss’ offspring would come with certain perks, but Mr Van Doren Jr suggests otherwise. “I remember painting the insides of the original factory with my brother and sisters,” he says. “Going with my brother and dad to paint the new store locations inside and out, building the shoe racks and placing all of the inventory and helping put up all of the displays.”

When he wasn’t hard at work, he and his four siblings would spend their days handing out flyers at swap meets to spread the word (in its initial phase, the company was operating with zero advertising budget). And, when they were done with school for the day, they’d tally up the stock for the company’s books.

“It’s been a family business since the beginning,” explains Mr Van Doren. His father, too, was notoriously hard-working. “My dad has always been very hands-on and involved. In the early days of building the factory, he had on overalls each day, getting dirty,” he says. And his can-do attitude applied as much to ensuring the design of the sneaker stood out in a crowded market, as it did to getting the factory up and running.

Vans was certainly not the first company to think that making canvas and vulcanised rubber deck or boat shoes, as they are variously known, was a good idea. Like other big names in the business, Mr Van Doren Senior’s previous employer was already producing something similar. “He knew… he had to build a better shoe,” says Mr Van Doren. And that started with the sole. Twice as thick as the competing brands, the original Vans #44 sneaker used pure vulcanised crepe rubber with a signature waffle underside, which rendered it extremely hard-wearing and provided a great deal of extra grip and traction. “Everything was designed and built to make our shoes wear longer,” he says. With an impressively sturdy shoe in its arsenal, it wasn’t long before the skateboarders came knocking.

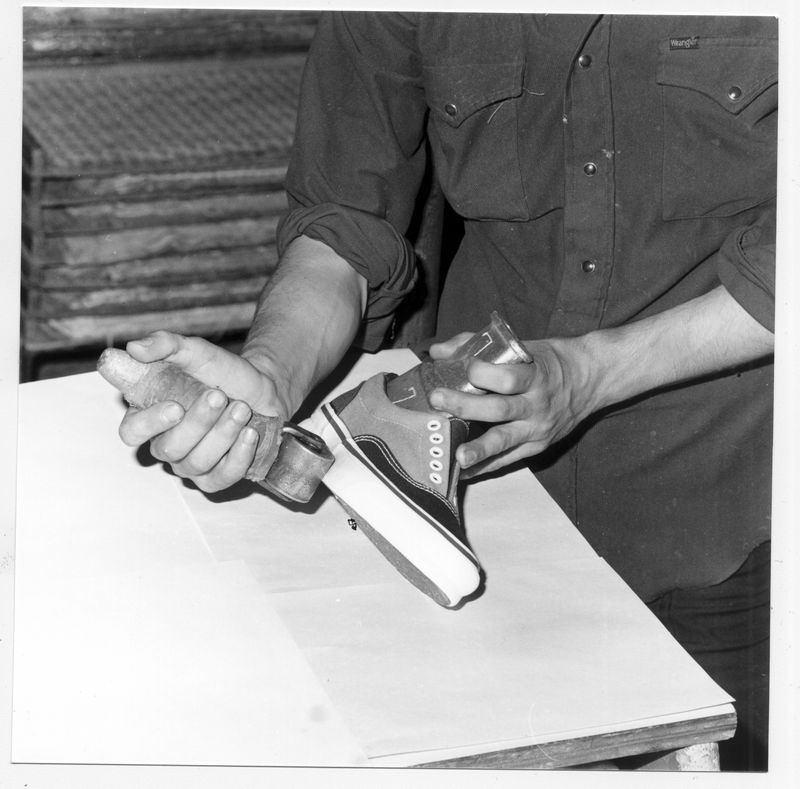

Roller for sticking down the foxing strip, Anaheim Factory, California. Photograph courtesy of Vans

It’s rare these days, in an age of bullet-pointed business plans and 360-degree marketing campaigns, that a brand finds its niche by accident. But skaters flocked to Vans without there being any need for the company to curry their favour. “They naturally adopted us,” says Mr Van Doren of up-and-coming skaters and Z-Boys Messrs Tony Alva, Stacy Peralta, Jim Muir and Jay Adams.

During the 1960s and 1970s, many companies were experimenting with producing lightweight shoes to cater to a growing demand for running and jogging sneakers. The precise opposite, then, of what skateboarders needed from their footwear. Vans was more than happy to oblige: “They saw that the fit of our shoes was better and were attracted to the sticky waffle [sole], since it gave the best board grip and feel,” says Mr Van Doren. “When the skaters and surfers began wearing Vans in the early 1970s, it helped make the shoe stylish and gave our brand purpose. Which is why, today, we continue to support them just as they supported us.”

Vans’ HQ at the centre of the skating’s spiritual home was certainly a plus, too. The popularity of the sport in California was, according to Ms Elizabeth Semmelhack, a sneaker historian and senior curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, intrinsically tied to the state’s surfing culture. “Those ideals of freedom on these two different vehicles – surfboard and skateboard – are two really important ideals of postwar American culture. And they’re developing simultaneously [in California],” she says.

Mr Van Doren agrees, adding that the laid-back SoCal lifestyle, with its warm weather, beaches and skate-friendly sidewalks, was a major factor in the company’s eventual success. “Being in the right place at the right time definitely helped,” he says. “I am so glad my dad didn’t stop off in the Midwest when he left Boston.”

“Vans has historically tapped into those ideas, that we don’t need bells and whistles, we just need to get the shoes on our feet and go do our thing”

Another of the #44’s biggest draws, and a USP that the brand still banks on today with its Design Your Own Vans® service and archive of big-name collaborations, is that the style can be personalised. The story of how the first pair of custom Vans came to be (a woman walked in and asked for a bespoke pair of sneakers crafted from her favourite fabric, for the added sum of 50 cents) sounds a lot like sneaker lore, but Mr Van Doren confirms the tale’s veracity. “Nobody knew who Vans was or what our brand was about, so we did almost anything to help put a pair of Vans on somebody’s feet, and that included offering customs,” he says.

The approach was not novel, but it was one that had been left behind by many clothiers and shoemakers, as mass-production methods took over after the industrial revolution. “That is part of their interesting origin story,” says Ms Semmelhack. “In some ways that makes Vans a more traditional shoemaker… they were small enough [that] they could be responsive and do what shoemakers have done forever, which is build the customer what they want.”

The #44’s simplicity and capacity for modification has given the style an enduring appeal – it remained the brand’s number one style until 2005 and, to this day, is one of its top five best-selling models, up there with the slip-on, Era and Old Skool. “The reasons why people gravitated towards Converse and Vans was because they weren’t hype. They’re anti-fashion to some degree. They’re about authenticity,” says Ms Semmelhack.

And there’s that word: authenticity. Leading us nicely to the sneaker’s change of name, which came about after Mr Paul Van Doren had parted ways with the brand. “I think it’s interesting… that they used the word ‘Authentic’,” says Ms Semmelhack. “Vans has historically tapped into those ideas, that we don’t need bells and whistles, we just need to get the shoes on our feet and go do our thing.”

And you can’t ask for much more than that from your favourite pair of sneakers, can you?