THE JOURNAL

Swordfish Brochettes. All photographs courtesy of Bloomsbury

The best recipes from the Muslim world, according to author and chef Ms Anissa Helou.

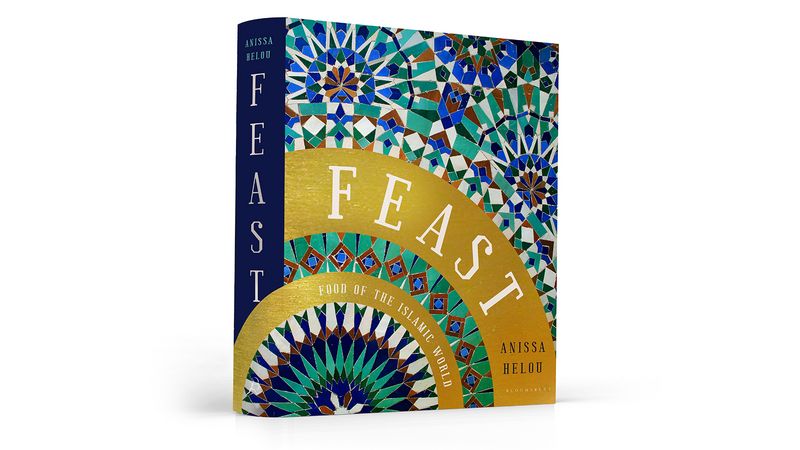

Feast: Food Of The Islamic World, broadcaster and writer Ms Anissa Helou’s ninth cookbook, offers a fascinating insight into the food cultures of Muslim-majority nations, spanning the globe from Senegal to Indonesia. It is an elegant, in-depth, culinary epic, composed of historical snippets, as well as more than 300 recipes for everything from Zanzibari doughnuts to Emirati-style roast camel hump, and gives glimpses of daily life across the Middle East and Arabian Peninsula, north-west China, south-east Asia, and (mostly northern) Africa.

Ms Helou opens Feast with the birth of Islam in Mecca, an oasis in the seventh-century Arabian desert, including detail of the Prophet Muhammad’s favourite meal: tharid – meat and vegetable stew on dry bread, variations of which still persist – before sharing a digestible overview of the faith’s evolution. Alighting upon the caliphates that spread Islam throughout the Levant, Maghreb, Iberian Peninsula and beyond, Ms Helou details how – via conquest, trade routes such as the Silk Road, and peaceable flows of populations – novel ingredients, indigenous eating habits and canny cooking methods informed Islam’s culinary lexicon, from the reign of the Omayyads (661-750) to the last major Muslim dynasty – the Mughals of the Indian subcontinent (1526-1827).

It was under the rule of the Baghdad-based, Persian chef-favouring Abbasid caliphs (750-1258; 1261-1521) “that Muslims started to develop a rich, culinary tradition,” Ms Helou says. Because: “Persian cuisine is the ‘mother cuisine’.” Ms Helou also deftly illustrates how the societies of North Africa, Turkey and Central Asia borrowed from the Persians, before the era of the Ottomans began and “a new culinary influence was born”. Having devoured the native cuisines of their subjects and availed themselves of New World ingredients, hundreds of Ottoman cooks simultaneously perfected dishes in the humungous Topkapi Palace kitchens in Istanbul, before regularly serving them to thousands of noblemen, and, during the holy month of Ramadan, the wider populace, allowing their creations to be reinterpreted. As for the Mughals (of the Indian subcontinent Mughal empire), Ms Helou states that their rarefied appetite for the arts was also evident in their dining habits, and that they, too, owe a debt to the Persians for their intoxicating, toasted spice-heavy cookery.

Broad bean salad

This handsome tome details manifold regional distinctions of flavour palate and dining custom. But, beneath any differences, what binds the Muslims of Morocco to the Iraqis, the Omani Arabs to the Bengalis – are, naturally, the tenets of Islam, many of which, especially around religious holidays such as the two Eids (al-Fitr and al-Adha), feature communal meals. “Food, hospitality and conviviality are absolutely central to [Muslim] life,” says Ms Helou. “In Feast, I quote the Prophet in the Quran telling his followers that is a duty to God. It’s still widely a traditional world, and, almost everywhere, people come together to cook… especially at [special] times, such as Ramadan, when there’s this huge contrast between the day, when you fast, and the night, when everybody gathers to enjoy their family and friends’ company… In Abu Dhabi, there was a Sheikh who had commissioned a catering kitchen to produce 3-4,000 meals to give out in a mosque for the entire 30 days. So, this person was paying to feed those who either didn’t have enough, or just wanted to participate in that amazing atmosphere [that transpires] when you sit down with hundreds of people to break the fast.”

Ms Helou reveals that only one dish is cooked in every Muslim-majority country – meat cooked on a skewer, an invention of the Ottomans, known variously as “kebab”, mishkaki in Oman and Zanzibar, “satay” in Indonesia, as well as numerous variations on the savoury theme, eg, the potato starch-laden, Kashgar “kawap” of China’s Xinjiang province; Hyderabadi kebab, made with twice-cooked meat; Lebanese kafta and punchier Moroccan kefta, and the Mughal-originated, nargisi kebab. This is a hit in India to this day and was enjoyed by the Brits, before being reinterpreted as the (much blander) “scotch egg”.

Further, albeit briefer, international ties are also revealed. Take h’risseh, a slow-cooked Lebanese, grain and meat “porridge”, borne of the Persian kitchen, and something that the Iranians know as haleem and enjoy for breakfast (as does Ms Helou in Feast in a kitsch pink café not far from Tehran). It was adopted by the Turks as keskek, and spread through India and Pakistan. Over and over, throughout this culinary journey, Ms Helou transports readers from the very origins of Islam to its contemporary influences on the world’s plate.

(Mashbuss rubyan)

Qatari prawn risotto

Ingredients

60g unsalted butter 1kg raw king or tiger prawns (in shell), peeled or unpeeled as preferred, and rinsed. 100ml extra virgin olive oil 3 medium onions, finely chopped 3 curry leaves 1 tsp, ground turmeric 2 tsp, b’zar spice mixture (see recipe below) 1 tbsp, ground dried lime leaves 3-4 whole cloves 200g medium tomatoes, diced into small cubes 3 tbsp tomato paste A few sprigs of both fresh coriander and parsley, most stems discarded, finely chopped 3 cloves garlic, crushed to a fine paste 400g basmati rice, soaked in 2L of water with 1 tbsp salt for 30 minutes Sea salt

Method

Melt the butter in a frying pan over a medium heat. Add the prawns and sauté in butter for 2 minutes. Take off the heat.

Heat the olive oil in a large pot over medium heat. Add the onions and sauté for about 5 minutes, or until golden. Add the curry leaves, turmeric, b’zar, ground limes, cloves, tomatoes, tomato paste, herbs and garlic and stir for a minute or so.

Add 500ml of water, bring to the boil. Drain the rice and add to the pan. Season with salt to taste. Reduce the heat to low and simmer for 10 minutes. Arrange the prawns over the rice. Wrap the lid with a clean kitchen towel and replace over the pot. Steam the rice and prawns for 10 more minutes.

Stir the prawns into the rice while fluffing it with a fork. Transfer to a platter, and serve hot.

B’zar, Arabian spice mixture

Ingredients

75g black peppercorns 50g cumin seeds 25g coriander seeds 2 tbsp whole cloves 2 tbsp broken Ceylon cinnamon sticks 2 tbsp green cardamom pods 2 tbsp small dried red chillies 2 whole nutmegs 2 heaped tbsp ground ginger 2 tbsp ground turmeric

Method

Put the whole spices into a food processor or spice grinder and blitz until finely ground. Transfer to a bowl and add the ginger and turmeric. Mix well. Store in an airtight glass jar in a cool, dark place for up to a year, possibly longer.