THE JOURNAL

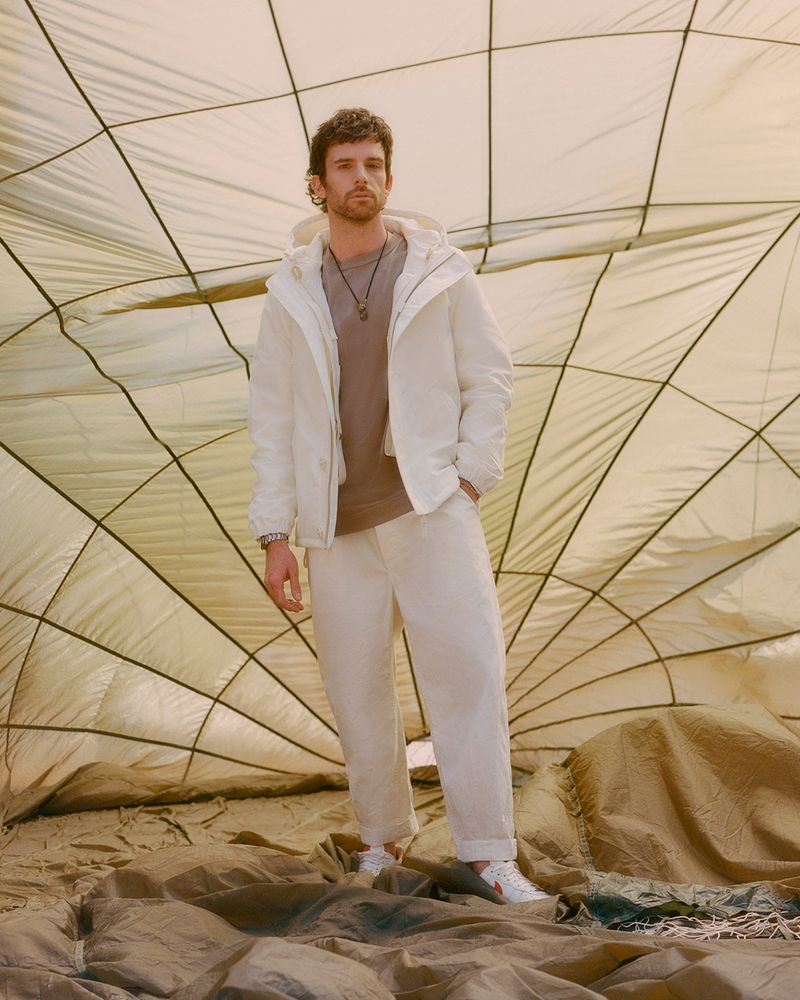

Applied Art Forms is a new brand with distinctive characteristics. The headline is that Mr Guy Berryman, who’s best known as Coldplay’s bassist, is the man, the money and the creative drive behind it. There’s a lot more to the brand than the fame of its founder, but it’s worth recalling the remarkable level of success Coldplay has achieved during its 25-year-history. Having emerged from London’s alternative rock scene in the late 1990s, the group has, over the course of eight albums, sold 100 million records. It is Berryman’s passion for architecture, design, engineering and utility clothing that truly distinguishes Applied Art Forms.

In preparation for this MR PORTER shoot, a Zoom call connects Berryman’s country house in England’s Cotswolds area to my home near Edinburgh. My location nudges Mr Berryman, who was born in Kirkcaldy, Fife, in 1978, to tell me that he went to school in Edinburgh until he was 13. “Which I hated,” he says. “It was very old fashioned, my days were very long. I had to get a train to Edinburgh at 6.20am, do the school day and then get the train home. That’s a long day in winter, in shorts. But actually I love Edinburgh and I do quite a lot of driving in Scotland.”

Cars are important to him. “I’m passionate about all things mechanical, whether it be pre-war tools, watches, cars and engines. I grew up loving machinery. My father was an engineer and I was studying to be an engineer.” It was while he was studying that Coldplay signed a five-album record deal in 1999.

Many people would happily swap the life of an engineer for global success, fame and enough money to build a car collection that includes a Bugatti Veyron, a Ferrari 275, 365, Dino and F40, a McLaren F1, a Zagato-bodied Porsche 356, a Lamborghini Miura and an Aventador. (His daily driver is a Land Rover Defender for its towing capacity.) But a few years ago, as a milestone loomed, Berryman wasn’t entirely comfortable with all of the choices he’d made.

“I was approaching 40 and it’s a point of reflection,” he says. “The questions I posed myself were: am I doing enough? Have I done enough? Am I making the most of the tools I’ve been given in life? The answer was that there was something missing, and it was the design process.”

Given his love of hand-built, beautifully engineered mid-to-late 20th-century objects, such as cars and furniture, was it immediately clear that he wanted to embark on a clothing project?

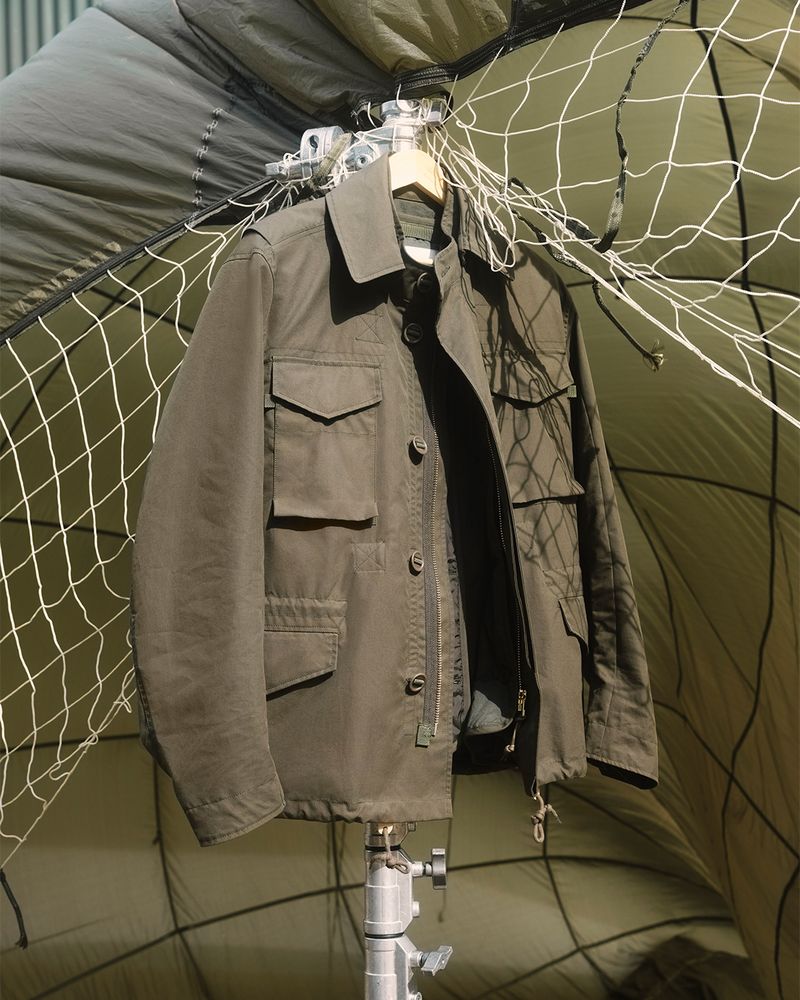

“It was surprising,” he says. “It would have made more sense if I’d made lamps, given my engineering background, but I’m so passionate about these old garments. One of my obsessions is for military utilitarian clothing. I was looking at my archive one day and I saw a wealth of ideas that could be interpreted, which would allow the creative process to begin.”

Berryman has, in the three years since that moment of self-assessment, discovered the challenges of running a nascent brand.

“My expectation was to sit at a table and design garments and build a very small team around me,” he says. “The reality is very different and it bites quite hard. I find myself having to approach so many disciplines that I never imagined, such as production processes, building an e-commerce platform, building a website and getting the payments systems set up. At times, it’s felt like a multi-disciplinary battlefront.”

It’s clear that Berryman is all in and that he reaps the rewards that are only available because he’s totally committed to the project. “There have been times when I’ve questioned whether Applied Art Forms is a good idea, but when I hold or wear something we’ve made, I feel tremendously proud.”

The clothes are inspired by his extensive collection of military and utilitarian clothing and 1990s-era pieces by celebrated designers Mr Helmut Lang, Mr Martin Margiela and Ms Katharine Hamnett. So are his clothes the fashion equivalent of musical cover versions?

“We’re not making replicas,” he says. “But we might combine the silhouette of one style with the details of another. And then we might elevate the construction details. When it comes to manufacturing and stitching and detailing, we’ve managed to do something quite special, and the quality of the materials sits alongside most luxury brands.”

“In 70 years, somebody might be wearing an Applied Art Forms parka. It’ll be all worn and faded and it might still be a covetable item”

“My focus is on longevity,” says Berryman. “I try to create styles that are relatively timeless, made from materials that will last and age beautifully. When you’re putting a new garment into the world, you have to ask: is it going to be worn and how long is it going to last?”

This explains the brand’s focus on natural materials. “One of the most important pieces in my collection is a cotton RAF parka from 1950,” he says. “The way it’s aged has made it more beautiful. It’s worn and faded like denim.”

Another vintage piece, a rare mid-century Beaufort life jacket, is also a rich source of inspiration. “It’s the single most complicated garment I’ve ever seen, with zips and flaps for oxygen canisters and inflatable devices,” says Berryman. “It provided all the details for our outerwear.”

It also sets an example in terms of quality control. “Instead of traditional buttons with four holes, the bar buttons are attached to a nylon webbing that’s stitch-reinforced on the back. When the pilot lands in the water, he can’t have all the buttons pop off because he’s going to die. The challenge we gave ourselves for our parka was to incorporate as many of these details as possible. There are many parkas out there, but none has this kind of detailing.”

Berryman has worked hard to get the small things right, but he’s equally concerned with how the clothes look and feel. Was it easy to nail the Applied Art Forms fit? “It was a real eye-opener,” he says. “Ready-to-wear clothing is hard because every human body is a different size and shape. We take inspiration from these old garments, but modernise the dimensions. I have a pair of Swedish military fatigues that are massive, but the width around the legs feels really nice, so for our cargo pants we kept the volume in the leg, but pleated the ankle and brought the waist in. So you have the space, but with something that fits around your waist and has a tapered fit. Applied Art Forms is more in tune with what’s going on in Japan and Korea at the moment than some of the European or American brands.”

The brand launched quietly last October, amid the pandemic. “I didn’t want to wait, so we launched with half a collection. It’s given us time to figure out how it works,” Berryman says. “This September, we’re launching more styles and it looks like a fully fledged collection.”

New this autumn are big blue jeans. “It’s a completely different silhouette [from normal jeans]. I designed it because I couldn’t find it anywhere in the market. They’re loose around the leg but with a waist that fits.” There’s an equally unconventional suit. “I don’t like the space a traditional suit can put you into. Our suit can work for a wedding or a dinner, but feels relaxed and comfortable. We used Ventile cotton, the jacket has patch pockets and the trousers are very loose, with a drawstring. I’d wear it with a T-shirt and a pair of trainers.” There are also a Ventile field jacket and a hand-finished yellow rucksack, inspired by Berryman’s vintage life jacket, in the works.

Applied Art Forms is a singular proposition because Berryman is a man of singular qualities. He looks at fashion with an aesthete’s appreciation of form and appearance, but with an engineer’s exacting approach to materials and construction. And he’s far more serious about the project than one might expect a rock star to be. What drives him is a restless curiosity and an ambition “that in 70 years somebody might be wearing an Applied Art Forms parka. It’ll be all worn and faded and it might still be a covetable item.”