THE JOURNAL

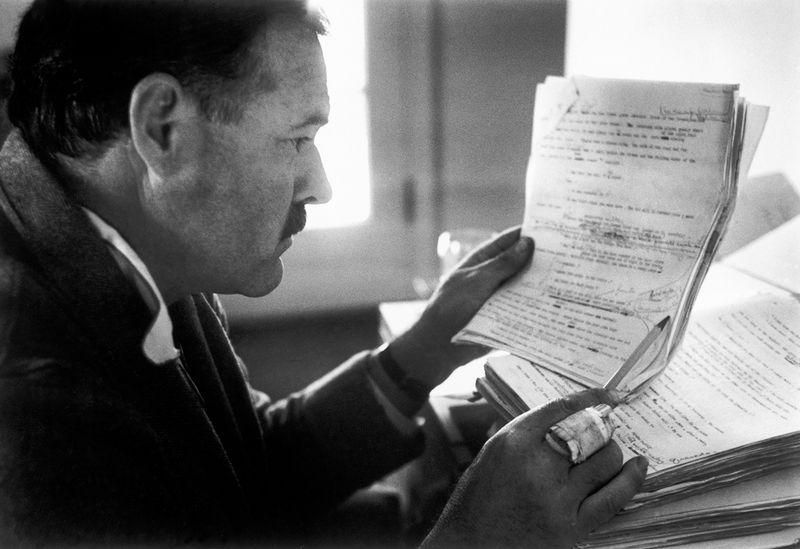

Mr Ernest Hemingway in Sun Valley, Idaho. 1940. Photograph by Mr Robert Capa. © International Center of Photography/Magnum Photos

From Mr Truman Capote to Mr PG Wodehouse – the literary figures with the most fascinating legacies.

Literary addiction can be a terrible thing. First, you make your way through a writer’s masterpieces. Then, his or her lesser works, perhaps in chronological order. Maybe there’s a letters collection, or – god forbid – a volume of light verse. Sooner or later, you have consumed a writer’s every published word, and possibly (via some quasi-reputable sources) a few unpublished words, too. In such a moment, even in our digital age, one must seek satisfaction by doing what our likeminded forefathers have done: heading to the archives.

Never before has so much work been so readily available to the literary enthusiast, even if exploring it requires a modicum of work (and often a plane ticket). Much of it is (or will be) digitised, yes, but most of it is not, and instead requires a pilgrimage to whichever Mecca your literary hero has chosen to bequeath or sell their papers to. (These can actually make massive profits – in 2016, Mr Bob Dylan sold his Nobel-worthy archive to the University of Tulsa for upwards of $15 million.)

Sometimes, the pairing of author and destination makes sense. For example, the archives of that ultimate New York street poet, Mr Lou Reed, are now housed at the New York Public Library. Sometimes, the connection is, shall we say, less than intuitive. To peruse the 68 boxes of papers – including one unpublished manuscript and three other near-finished novels – of Mr Kingsley Amis, that most English of satirists, one must commute to the Huntington Library in San Marino, California.

In any event, a true devotee owes it to himself to explore his icon’s drafts, notes, diaries, and doodles in person. There is something mystical about seeing these manuscripts, and something comforting about knowing even your favorite literary lion sometimes struggled to confront the blank piece of paper before him. Here, then, are seven writers’ collections worth the journey.

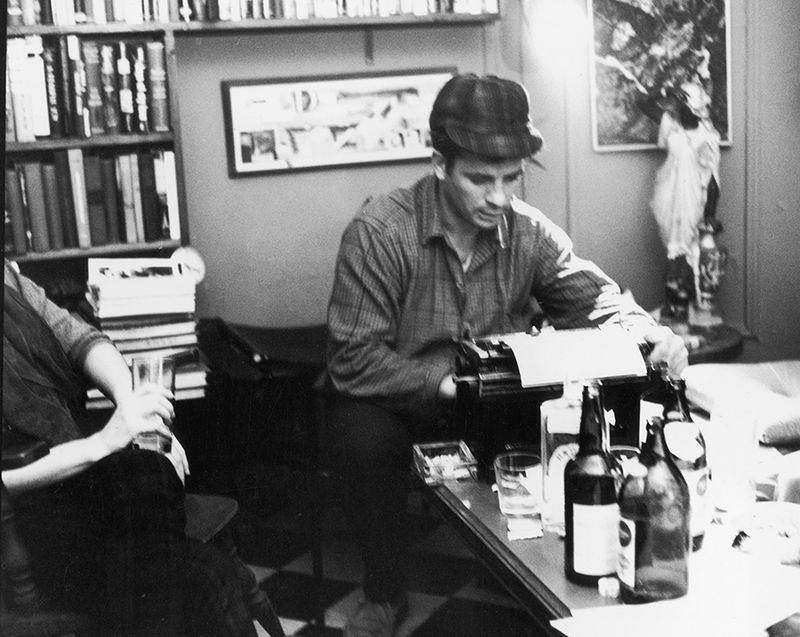

Mr Jack Kerouac’s On The Road journal

The Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, US

Mr Jack Kerouac types a poem in New York, December 10, 1959. Photograph by Mr Fred W McDarrah/Getty Images

There is a saying among literary archivists: “Two things are inevitable: death and Texas." That’s because the Ransom Center in Texas has been an aggressive acquisitor of literary collections, amassing a trove that includes Messrs Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s notes from their Watergate reportage; the archives of Mr David Foster Wallace, Mr Norman Mailer and countless others. But the highlight is a spiral notebook belonging to Mr Jack Kerouac, one that includes his notes for On The Road. Inside, you’ll find everything from handwritten prayers to, on the final page, a list of crops Mr Kerouac planned to grow on a farm with Mr Neal Cassady. The farm plans never bore fruit; the notebook most certainly did.

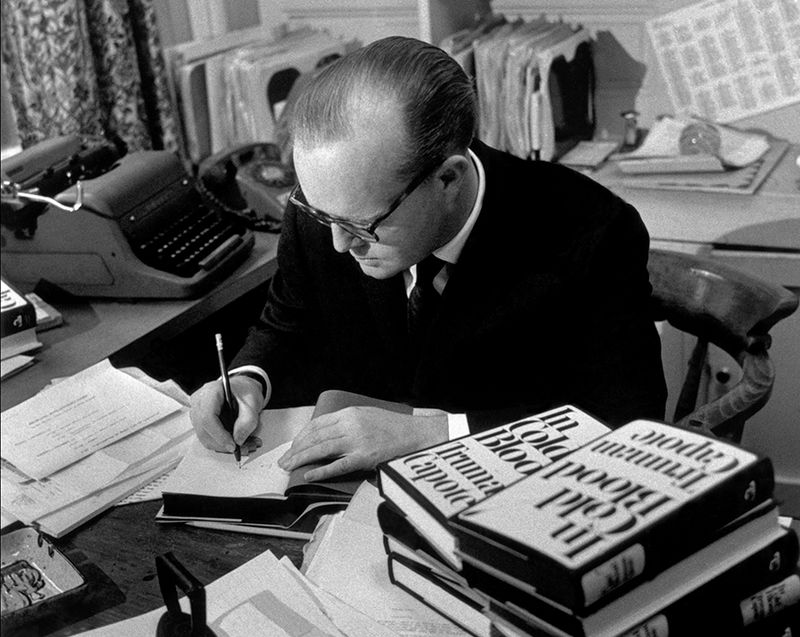

Mr Truman Capote’s archive

The New York Public Library, US

Mr Truman Capote signing copies of his book in the offices of Random House Publishing, New York, 1965. Photograph by Mr Bruce Davidson/Magnum Photos

Mr Kerouac had perhaps no greater literary nemesis than Mr Truman Capote, who famously described On The Road as not writing, but typing. Mr Capote’s own typing – in the form of nearly 40 boxes of papers – is housed inside the NYPL’s legendary collection. Of particular interest is Mr Capote’s collection of material on the 1959 murder of the Clutter family, which he used in writing In Cold Blood. The archive includes letters he wrote to Mr Alvin Dewey, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation’s chief detective whose cooperation had an incalculable impact on Mr Capote’s literary breakthrough.

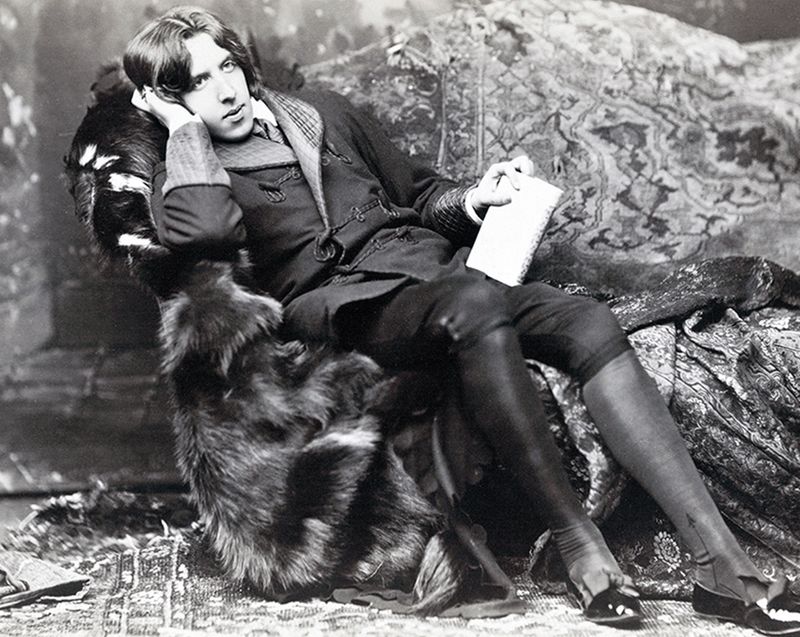

Mr Oscar Wilde’s archive

University of Leeds Library, UK

Mr Oscar Wilde, circa 1884. Photograph by Mr Napoleon Sarony/Universal Images Group/Getty Images

Mr Oscar Wilde famously called his diary something sensational to read on the train; it turns out his letters make for sensational reading, too. In his ornate, almost indecipherable script, he addresses friends and colleagues in brief notes accented with doodles and drawings, revealing a witty and tender side. You can also find an extensive collection of manuscripts here. Should you crave more unpublished Wilde, his archive has been rather promiscuous, with papers at the New York Public Library and at the aforementioned Ransom Center in the US.

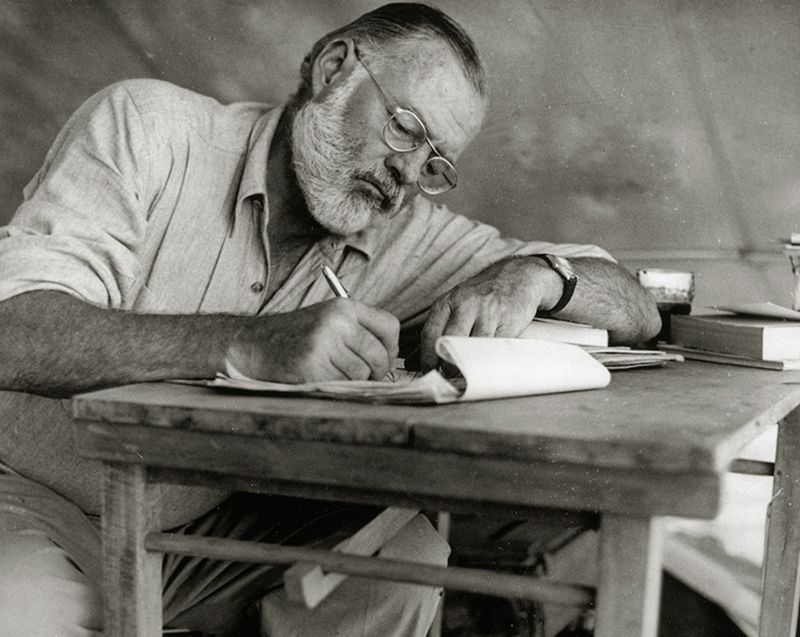

Mr Ernest Hemingway’s archive

The John F. Kennedy Presidential Library, Boston, US

Mr Ernest Hemingway writing at a campsite in Kenya, circa 1953. Photograph by LFI/Photoshot

Mr Ernest Hemingway and President John F Kennedy never met, but the latter was an admirer of the former, and members of the two troubled families came to know each other over time. Mr Kennedy arranged for Mr Hemingway’s widow to enter Cuba and reclaim her husband’s belongings following his death in 1961. That he did so after the Bay of Pigs debacle is a testament to both his power as a statesman and his status as a Hemingway fanboy. While it might be an unusual experience admiring Mr Hemingway’s handwritten drafts and childhood scrapbooks inside a memorial to the slain president, that’s exactly how Ms Hemingway intended it: a place where Mr Hemingway “would be to himself and have a little personal distinction.”

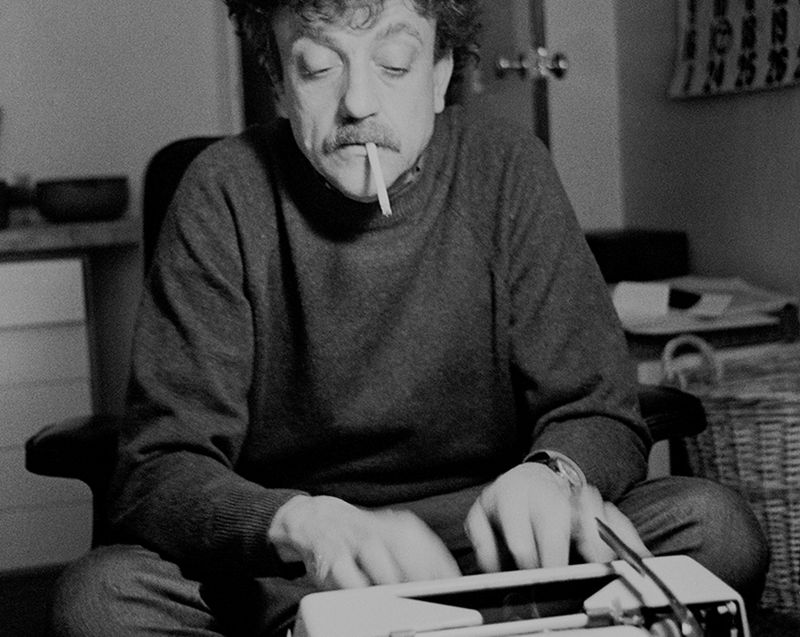

The archives of Mr Ian Fleming and Mr Kurt Vonnegut

Indiana University, Bloomington, US

Mr Kurt Vonnegut at home, April 12, 1972 in New York. Photograph by Mr Santi Visalli/Getty Images

One was an elegant writer of iconic spy novels, the other a disheveled master of brooding satire, and yet both haunt the library here. For Mr Kurt Vonnegut, this was a homecoming – the Indiana native is a revered figure in these parts. (Make sure you visit the Vonnegut Memorial Library in nearby Indianapolis, and enjoy a cocktail at the Vonnegut-inspired Bluebeard restaurant.) At the University of Indiana’s Vonnegut archives you can peruse nearly 6,000 items, including drafts of all of his major works. When it comes to Mr Ian Fleming meanwhile, the collection has the original manuscripts of 11 Bond novels (not to mention Bond ephemera from 007’s cinematic incarnations), but the highlight is Mr Fleming’s personal library: he collected first editions of various scientific publications. Presumably this is where he got the idea for the space-bound villain’s lair in Moonraker.

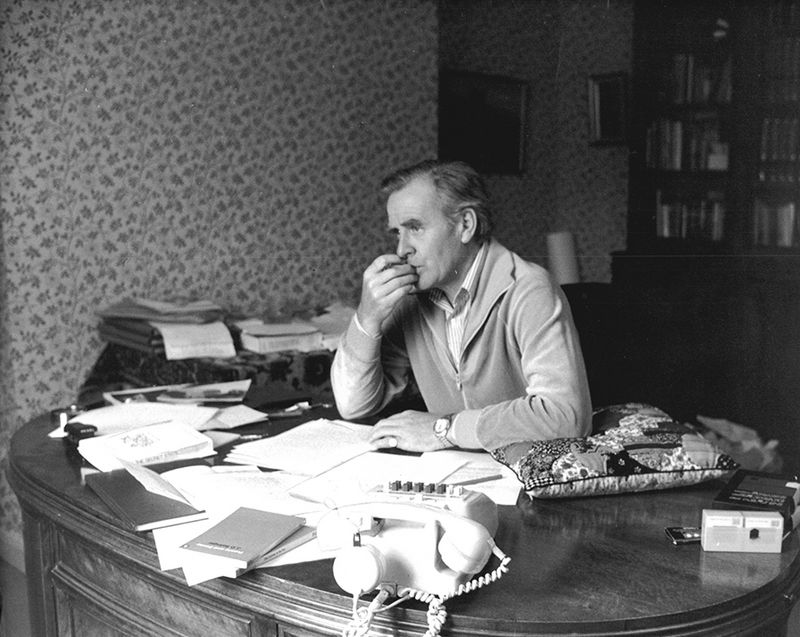

Mr John le Carré’s archive

Bodleian Libraries at the University of Oxford, UK

Mr John Le Carré at his desk, 1 Oct 1979. Photograph by Mr Monty Fresco/ANL/REX/Shutterstock

On a very pink piece of unlined paper in this collection, Mr John le Carré repeatedly scratched out words, scribbling new ones on top of them, next to them, over them, even adding a walled-off section of prose at the bottom left of the paper. There’s an arrow here, a bit of red scribble there. The goal of this meticulous work? A description of Mr George Smiley, the legendary intelligence officer at the heart of Mr Le Carré’s best work. (“His gait anything but agile…”) The line was destined for The Reluctant Autumn Of George Smiley, which you may know under its eventual title, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. That’s just one reason to visit – the library is also home to the work of countless more British writers, including Ms Jane Austen. Mr Smiley recently returned in Mr Le Carre’s latest novel, A Legacy Of Spies.

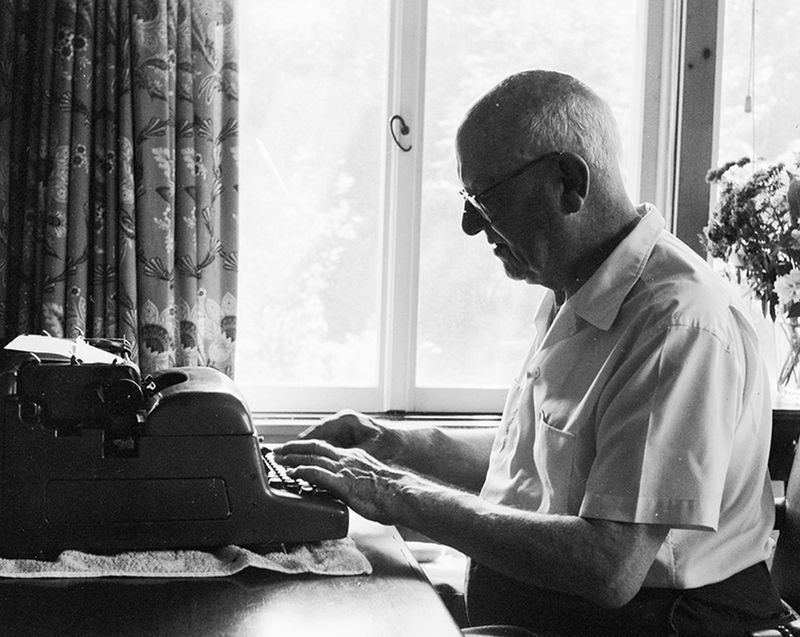

Mr PG Wodehouse’s archive

The British Library, London, UK

Mr PG Wodehouse at his typewriter at home in Remsenberg, Long Island, New York, 1 August 1968. Photograph by Mr F Roy Kemp/BIPs/Getty Images

More than 40 years after his death, and 70 years after he permanently left England for the US, the prolific author’s papers have finally returned home, taking their rightful place alongside those of Mr Evelyn Waugh and Ms Virginia Woolf. You can discover how much painstaking effort was behind his seemingly effortless words. However, the real prize here is the materials related to his internment by the Nazis, a period tarred by Mr Wodehouse’s ill-advised appearances on Nazi radio, making jokes and assuring audiences he was fine. (As The Observer noted late last year, a later British report “exonerated him of everything except stupidity”.) The controversy sparked Mr Wodehouse’s self-imposed exile; the return of his archives are a welcome opportunity to revisit, and reconsider, the master’s work.

PUT PEN TO PAPER

Keep up to date with The Daily by signing up for our weekly email roundup. Click here to update your email preferences