THE JOURNAL

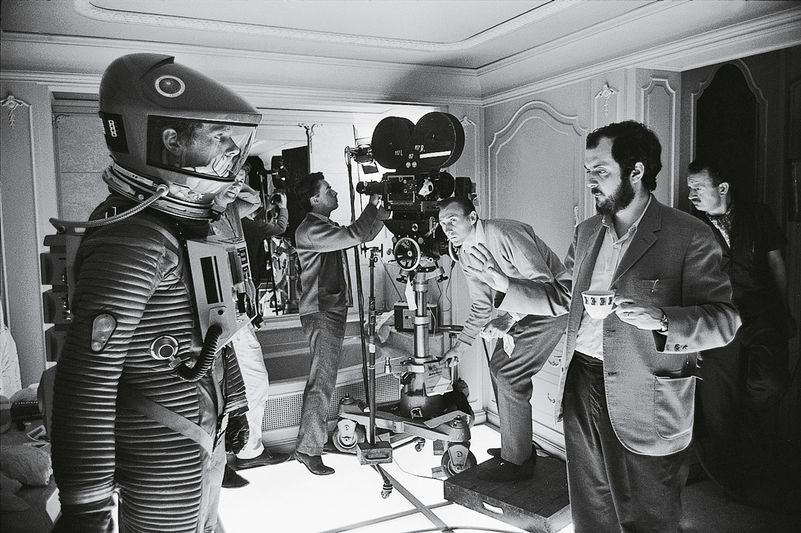

Mr Stanley Kubrick on the set of 2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968. Photograph © Warner Bros. Pictures. Courtesy Somerset House, London

Somerset House’s new exhibition maps the influence of the American director and screenwriter through artworks inspired by his remarkable legacy.

Mr Stanley Kubrick was the high priest of arthouse-as-mainstream cinema. His style – a movable feast of impeccable geometrics, cold, dense and dreamlike with a sense of humour that actor Mr Malcolm McDowell described as “black as coal” – transcended genres so successfully that it redefined them. Over 25 years, he reinvented comedy (Dr Strangelove), sci-fi (2001: A Space Odyssey), dystopian satire (A Clockwork Orange), period drama (Barry Lyndon), horror (The Shining) and even the post-Apocalypse Now Vietnam film (Full Metal Jacket). Primal and cerebral, his films chill, unwind, manipulate, stiffen and expand the mind, as irresistible to an Alabama truck driver as a Cambridge intellectual. The Shining, in particular, is an infinite mirror-hall of interpretations, from faked moon landings to Native American burial grounds.

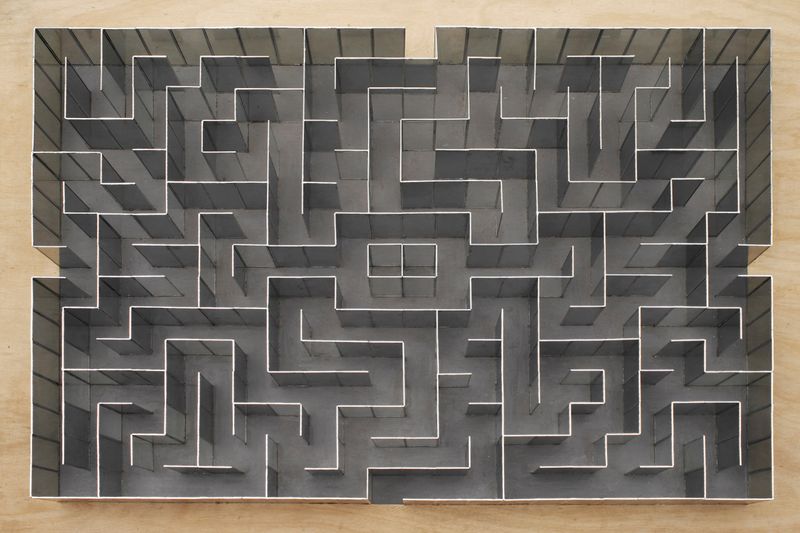

This week at London’s Somerset House (a neoclassical labyrinth that itself feels aptly Kubrickian), the new exhibition, Daydreaming With Stanley Kubrick, showcases works from contemporary artists inspired by the director. The most referenced films in the exhibition seem to be A Clockwork Orange, 2001 and The Shining. Mr Paul Insect and Mr Marc Quinn refract the 2011 London riots through the former, whose language, anarchic juxtapositions and grotesque eroticism prefigure The Chapman Brothers (the film, lest we forget, was banned for 26 years at the director’s request after spates of copycat violence). 2001, Mr Kubrick’s headiest film-as-religious-experience, elicits works as varied as Messrs Haroon Mirza and Anish Kapoor’s “Bitbang Mirror” installation; a short film written by Ms Samantha Morton; and fragrance designer Ms Azzi Glasser’s futuristic scent.

Symbols in The Shining, parsed for meaning ever since its release, are amplified here: the hexagonal pattern of The Overlook Hotel’s carpets cover an exhibition corridor, while Mr Iain Forsyth and Ms Jane Pollard (the artists behind Mr Nick Cave’s wonderful 20,000 Days On Earth) have made a “Requiem For 114 Radios”, a rework of the film’s title track with Mr Jarvis Cocker and Ms Beth Orton in a choir of singer-songwriters. A conspicuous absentee is Barry Lyndon, Mr Kubrick’s most painterly film, re-released in cinemas at the end of the month. With its groundbreaking use of natural light and Gainsborough-esque compositions, every frame is a rigorous work of art.

Left: ”Metanoia”, 2016 by Ms Polly Morgan. © Ms Polly Morgan. Courtesy Somerset House, London. Right: ”Twilight”, 2014 by Mr Doug Aitken. © Doug Aitken. Photograph by Mr Brian Forrest. Courtesy Somerset House, London

The influence Mr Kubrick has on his screen disciples is as voracious as ever (Mr Paul Thomas Anderson; Mr Christopher Nolan; Mr Gaspar Noé; even The Simpsons is said to have more references to Mr Kubrick’s films than to any other cultural canon), but what about his own inspirations? They come more obviously from non-cinematic art forms. To namecheck two of the novelists he adapted, he combines Mr Anthony Burgess’s chameleonic grandeur with Mr Vladimir Nabokov's meticulous, taboo-tormented flair (the ghostly acrostic at the end of Mr Nabokov’s “The Vane Sisters” foreshadows The Shining). Music, in Mr Kubrick’s hands, can reinforce his visual neatness (the Mr George Frideric Handel in Barry Lyndon) or illuminate unexpected pockets of chaos (the use of Mr Ludwig van Beethoven in A Clockwork Orange). But his sense of design, mood and iconography particularly overlaps with the history, and future, of art – which makes this week’s new exhibition so pertinent.

”The Shining”, 2007 by Mr Gavin Turk. © Mr Gavin Turk. Photograph by Mr Andy Keate. Courtesy Somerset House, London

Why is Mr Kubrick such a fascinating figure, still? His films were both genuinely popular and creatively uncompromised, the Holy Grail of artistic success. He increasingly embraced mystique and dream-logic (Eyes Wide Shut plays like one long psychogenic fugue), and Mr David Lynch, whose Eraserhead Mr Kubrick adored, is his closest heir (attempts to “decipher” Twin Peaks and Mulholland Drive command a similar fanaticism to The Shining). His private life had a mannered, Pynchonesque secrecy that only heightened the intrigue. But at home, he was a shy family man with a love of cardboard boxes, watermelons and Ryman Stationery. He was a compass rose perfectionist, a visionary pedant, a reluctant master of his own mythology, the obsessive wizard behind the curtain. We still have a hell of a lot to learn from him, and this exhibition is another step in the right direction.

Daydreaming With Stanley Kubrick is at Somerset House now